- Part 1 Broadcast: Tuesday, 17th January 1984

- Part 2 Broadcast: Wednesday 18th January 1984

- Part 3 Broadcast: Thursday, 19th January 1984

Character: Sir Charles Marchington QC

Background

Crown Court was a British television courtroom drama series that was produced by Granada Television – part of the Independent Television (ITV) network. The first of 300 episodes[1] was broadcast in 1972, and ran until 1984.

Typically, a ‘case’ would be played out over the course of three 25 minute episodes, shown over as many afternoons. The court was set in the fictional town of Fulchester.

While the main characters were played by actors, the jury was made up by members of the public chosen from the Electoral Register. It was this group of people that would decide whether the character on trial was guilty or not guilty.

| Notes: [1]. ‘The Son Of His Father’ was episode 290. |

The Story

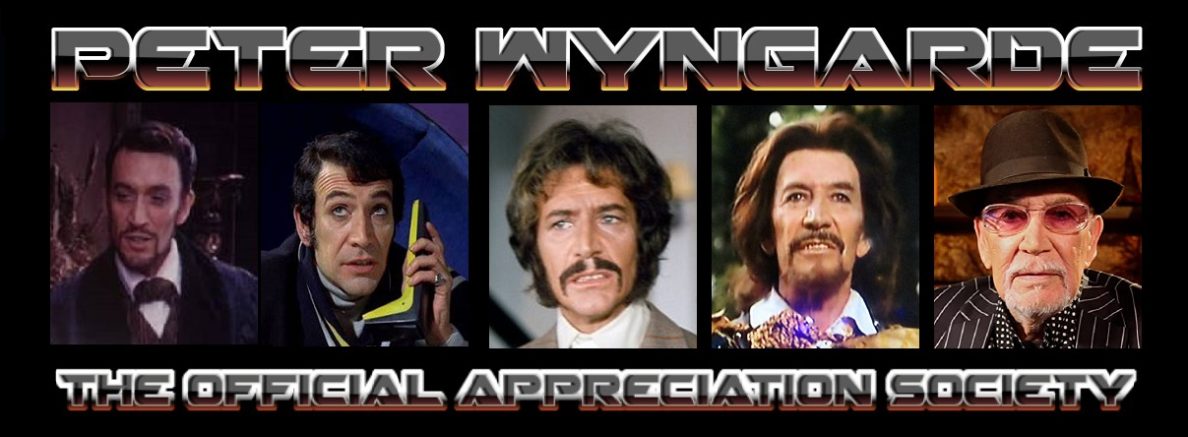

Left: Peter as Sir Charles Marchington QC

Sir Roland is the first to take to the witness stand, where he is questioned by Prosecution lawyer, Sir Charles Marchington QC (Peter Wyngarde), who enquires as to the nature of the relationship he’d with Ms Ginsel.

The elderly Lord explains that he and the young woman share an interest in stamp collecting – indeed, he had once been chairman of the Fulchester Philately Society, which is where he’d met Ms Ginsel. Latterly, she had acted as his advocate when bidding for rare stamps at auction.

Sir Roland admits to visiting the young woman at her home on several occasions, which he describes as a modest flat 15 miles from where he himself lived. There he had met the child, Gavin, and also one-time musician and photocopier salesman, Lee Sinclair – a friend of Ms Ginsel.

Despite receiving a number of rather familiar letters from Ginsel over the course of many months, including a somewhat accusatory note demanding the sum of £200 for the care of young Gavin, Sir Roland vehemently denies that his relationship with the young woman had been anything other than businesslike. He categorically denied that he was child’s father.

When Sir Charles completes his examination of the MP, Ms Ginsel’s defence lawyer – Eloise Hunter QC (Roselie Crutchley) – takes to the floor and immediately makes the charge that Sir Roland is the child’s father that in actual fact, he had been in an long-term, intimate relationship with the boy’s mother. She further contends that he had merely been using their mutual interest in stamp collecting as a foil; the fact that he hadn’t told his wife about Ms Ginsel’s numerous letters only confirmed this.

The next witness to take the stand is Jean Tomson – a middle-aged widow who lives in the same block of flats as Ms Ginsel. Sir Charles learns during his questioning that she had been a friend of the younger woman but that the two had recently fallen out. She insists that Ginsel and Lee Sinclair had been co-habiting for some time, saying that he was at the defendant’s flat “all the time”. She makes mention of an incident some months earlier when she’d seen Sinclair sitting on the stairs, crying, and that Ginsel was attempting to comfort him.

When cross-examined by The Defence, Mrs Tomson is obliged to reveal that she herself had been involved with Lee Sinclair, which prompts the accusation that she is in fact jealous of Ginsel and that her agreeing to act as a witness for the Prosecution had come out of malice. Tomson refutes this.

Following Sir Roland’s resignation from the Philately Society teacher, Leonard Alldis (John Quentin), had taken over as Treasurer. He is next to step into the witness box.

He tells Sir Charles Marchington that it had been common knowledge within Society circles that Lee Sinclair was the father of Mary’s baby, as she herself had told anyone who cared to listen. However, the court is stunned to learn that Ginsel had been pregnant, not once but twice. It was when she began to attend group meetings that Mr Alldis himself had gone to her home to check on her as he and other members of the Society were concerned about her. At that time, she’d told Alldis that Sir Roland was the father of the child she was expecting – claiming that he’d seduced her and then left her to fend for herself. As a long-time acquaintance of the MP, Allis had found this difficult to believe.

When the teacher had next seen Mary, she was no longer pregnant. He was described her as “hysterical” and that she’d claimed that the whole thing had been a “mistake”.

Mr Alldis latterly admits to Elois Hunter during her cross-examination, that there had been rumours about Mary and Sir Roland circulating amongst members of the philately group for months before he resigned.

The next witness to be called to the stand is Alisdair Miller (Andrew Downie) – editor of the Fulchester Recorder newspaper. He remembers receiving a letter from Mary Ginsel accusing Sir Roland of failing to send maintenance payments for her son. However, instead of publishing the note Miller, who had been a good friend of the MP for around 15 years, called Sir Roland to inform him of it’s receipt. Some days later, Mary had called the newspaper office to ask for the letter back, as she wished to retract her allegation.

When asked by Sir Charles whether he had believed the contents of the letter, Miller said he did not: “It was not Roland’s style,” he replied.

At last, Mary Ginsel takes the stand. She confirms to Sir Charles that she is presently unemployed, but that she had previously worked as both a librarian and supply teacher. She had no criminal record.

She immediately refuted Sir Roland’s claim that it was she who had invited him to visit her home. In fact, she says, it had been very much the other way around; he had often turned up, uninvited. Beyond their shared interest in stamps, she had nothing in common with the older man and confesses that she didn’t really like him.

On either the second or third visit to the flat, she reveals, the MP had “made a pass” at her, and in spite of finding him creepy, she had gone to bed with him nonetheless. This had happened several times thereafter. Until then, she claimed, she’d had had no experience with men.

It was around the same time that she’d first met Sir Roland that Lee Sinclair had come into her life, and although they had become close, she denied having a sexual relationship with him. She did, however, admit that she’d told members of the Philately Society that he was the father of her son.

Ms Ginsel goes on to tell the court that, suddenly and without warning Sir Roland, who had agreed to forward her £200 in cash each month for the care of their child, stopped visiting and reneged on his promise concerning the maintenance money. Soon after she had lost her job at the library; she was destitute. Understandably, she was both desperate and angry – that is why she had sent the letters both to Sir Roland and the newspaper.

Sir Charles begins his cross-examination of Mary Ginsel by reading aloud the letter she had sent to Sir Roland Richardson – emphasising the section in which she’d threatened to contact the Fulchester Recorder should he fail to send her the £200 she insisted he owed her.

Sir Charles begins his cross-examination of Mary Ginsel by reading aloud the letter she had sent to Sir Roland Richardson – emphasising the section in which she’d threatened to contact the Fulchester Recorder should he fail to send her the £200 she insisted he owed her.

Sir Charles points out that she was not merely “requesting” for the payment but was, in fact, making threats to expose the MP and ruin his family life. If the young woman was so resolute in her arraignment of Sir Roland, why had she not simply instigated a Affiliation Proceeding against him so that there would’ve been no need for the letters? She was to cite a lack of money and the fact that she had not wanted to cause problems for Sir Roland.

Although she would claim to be destitute, she admitted under incessant questioning by Sir Charles, that she had not only been claiming Social Security benefits since losing her job at the library, but that the local authority had also been paying her rent. Additionally, Lee Sinclair who, she admitted had stayed with her between 5 and 10 times over a 6 month period, had also been giving her money.

The final witness to face Sir Charles’ questions is Lee Sinclair (Bill Nigh), who confirms to the court Ginsel’s story concerning the nature of their relationship, and that she had been there for him after he’d suffered a breakdown. Although he admits to staying at her flat on many occasions, he insists that he was not living there on a permanent basis as Jean Tomson had claimed.

He is also to confess that the medication he had been taking for his condition at the time had rendered him impotent, so he could not possibly be the father of Ms Ginsel’s child. Nonetheless, he had agreed to go along with her story that he was Gavin’s dad.

The Judge – Mr Justice Hamond (Donald Eccles) – directs the jury in his summing up that they must now decide whether Mary Ginsel is guilty of maliciously using threats to obtain money from Sir Roland or had merely been asking the father of her child’s for a payment she was entitled to.

When the jury return to the court room, the Foreman is asked to stand and give the verdict: NOT GUILTY.

Ms Ginsel is free to go.

© The Hellfire Club: The OFFICIAL PETER WYNGARDE Appreciation Society: https://www.facebook.com/groups/813997125389790/

3 thoughts on “REVIEW: Crown Court – ‘The Son of His Father’”